![]()

The things that torment us are usually invisible. Humans suffer from ailments that are intangible. If you think about the things that occupied your mind last night as you put your head to the pillow, you might find that you were pre-occupied by non-material, irrational things, such as love, happiness, elation, and excitement, or fear, confusion, worry, and anxiety. All good things and all bad things start out as non-existent states, and then they manifest into either burdens or blessings. The clever human is one who can foresee problems. Often, this foresight can be assisted if we learn to take heed of the signals that speak to us.

Here is the secret to better life-management and business-management: heed the insignificant signals. Learn to read the clues that do not necessarily present themselves in white-papers and green-papers. The astute will be able to hear the alarm bells, long before they ring. It’s like hearing a tune by looking at the score, long before the musician converts the notes into sounds. There are dozens, if not hundreds of clues that scream out at me when I walk through a client-site or a school or a hospital. Not all things in life speak English. Not all ailments have names. Similarly, not all corporate cancer is immediately visible. However, with x-ray vision and super-sonic hearing, you can avoid much of the drama. It’s a bit like Radio Moscow. This very minute, Radio Moscow, as well as the BBC and the ABC radio waves are bouncing off this very computer screen. At this instant, ambulance, fire, and police conversations are bouncing off the walls. You cannot hear them, but they are there. With the right receiver, you can decode the signals. If you do not have a receiver, or have no idea about radio signals, or if you do not know what the BBC is, nothing changes. The signals are ever-present whether you like it or not.

In business and in life, the signals are there. We just need to hone our decoding skills. Sadly, managers are so busy with systems and procedures and reports and paperwork, that they have no time to listen or to observe. And when they do see something suspicious, they are easily distracted because the signals might at first be weak or disjointed.

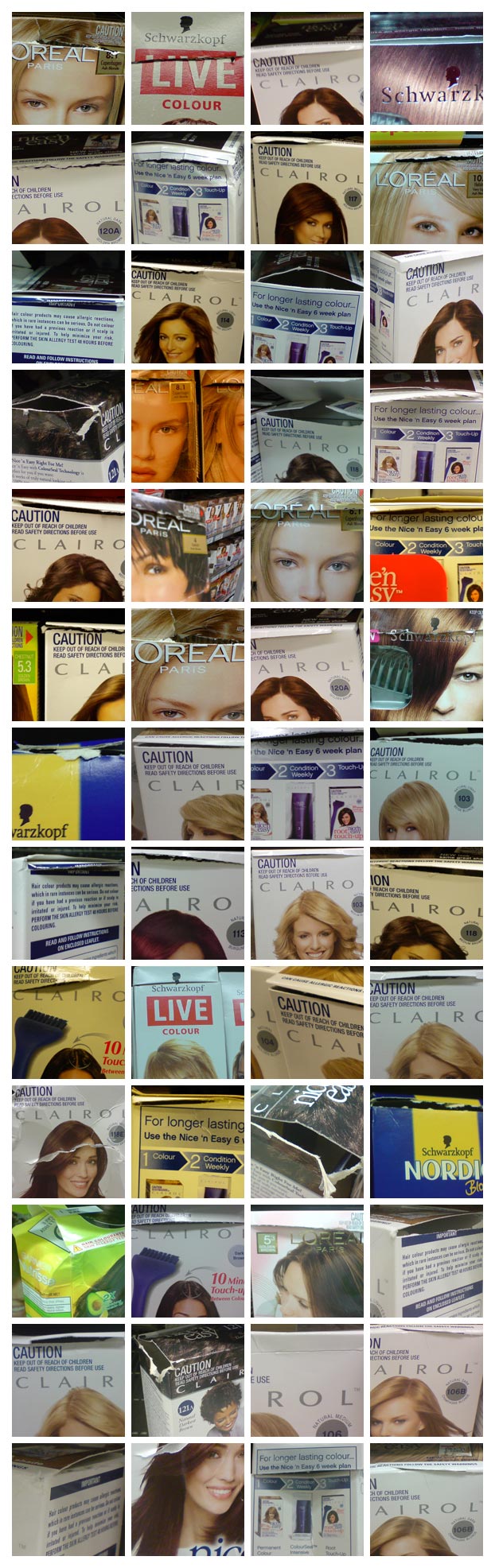

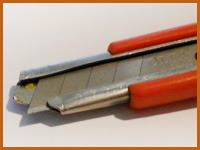

By way of example, consider that five years comprise 1825 days. For the past 1825 days and nights, I have, at random, frequented my local Woolworth’s Supermarket. I enjoy shopping there. Most of the time, the food is fresh and of good quality. The place is spotlessly clean, and most of the time, the checkout is rapid. However, for the past five years, I have been monitoring the hair-dye sections. Every time I visit the supermarket (which is more than twice per week), I walk past the section that sells hair colour products. It has become a ritual of disbelief. You see, every time I go there, I see a range of products that had been sliced open by someone who does not know how to use a cutting knife (see photos below). Retailers must open thousands of boxes. Usually, a knife is needed. Ideally, people should teach each other how to do things. Yet, I cannot understand why in five years, no-one has corrected this situation. It no doubt costs someone a lot of money. It could be that the outer boxes in which these products arrive are thinner than they ought to be, or badly designed.

I just cannot understand how no packer, no supervisor, no store manager, no merchandiser, no sales rep, no floor walker, no security officer, no financial controller, no staff member, no casual, no temp, no stock-taker, no cleaner, has noticed that these boxes are always, always, always, ripped by someone who does not know how to use a cutting knife. I am not complaining about cut boxes. I am raising the alarm at the deaf and blind. If something so obvious is not ringing alarm bells for anyone at Woolworth’s or at L’Oreal or at Schwarzkopf, it makes me wonder what else is being ignored. What other small, invisible, intangible, insignificant, irrational technicalities are being overlooked, which, in due course, will create difficulties, obstacles, and indirect losses or problems. All I am saying is that the clues are plentiful, whether they point to matters of the heart, the head, or the wallet. Maybe you can start by playing a game every Wednesday morning with all your staff. The game can be called ‘observation’. Place a hundred small objects on a tray. Ask the team to study the tray. Then, ask them to turn around, and remove one item, and then ask them to look again and see if they can spot what is missing.

Make sure that each of your staff members walks through each process (by working in different departments) so that they can see life from a different perspective. Start by calling your company’s phone number and listening to the music-on-hold. I bet it’s out of tune, and either no-one has heard it, or has not observed it, or has not noticed it, or has not cared about it, or does not know what to do about it.

![]()

![]()

Incidentally, when I was 13 years old or so, I worked at Woolworth’s after school and on weekends. I recall one of my first experiences with a cutting knife. I was on the shop floor, about to open a box, when a man twice my height towered over me and said, ‘Let me show you how to use that knife.’ The first thing he did was withdraw the blade until it just extruded. He said, ‘You are only trying to cut sticky tape on the box. All you need is the tiniest tip of the blade. That will do the job.’ Since those days, I have grown fond of such knives because I prefer them over scissors when cutting paper and card. I have had my horror stories with them. On my finger, I have a scar that I will take to my grave. I am now a seasoned knife cutter, after years of bitter experience. One of my friends nearly had his eye out, were it not for his glasses. This might help you to understand how my mind works, and why I was attracted to those cut boxes!

Comments are closed.