Everywhere we turn, there are advertisements. Yet, why do some work, while most don’t? As with any profession, advertising is both a science and an art. Unfortunately, the barriers to entry are minimal. Anyone can create an ad, whereas not everyone can build a jet engine. With basic cut-and-paste skills, graphic designers and in-house creatives fall in love with their own campaigns.

Everywhere we turn, there are advertisements. Yet, why do some work, while most don’t? As with any profession, advertising is both a science and an art. Unfortunately, the barriers to entry are minimal. Anyone can create an ad, whereas not everyone can build a jet engine. With basic cut-and-paste skills, graphic designers and in-house creatives fall in love with their own campaigns.

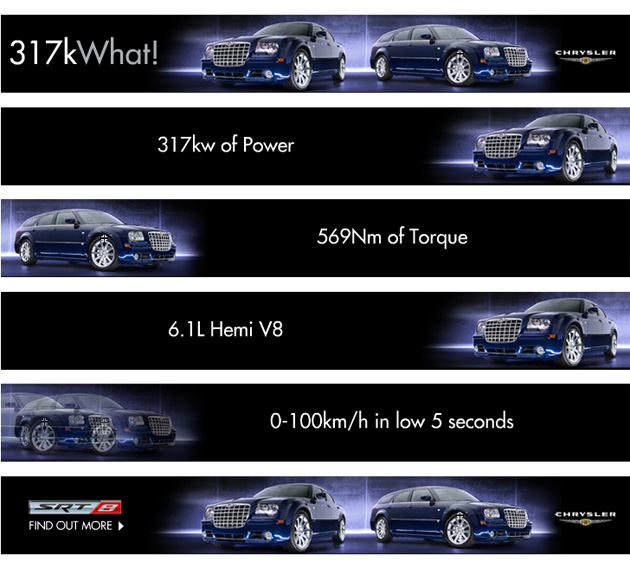

Over the years, Chrysler has been missing the mark (or should I say ‘Marque’ to force a pun, as many do, thereby committing sin Number One). The Chrysler advertisement below, which resembles one of their billboard campaigns, seems to ignore two important rules. Incidentally, while the world was suffering one of its greatest financial meltdowns, the US government poured millions into Chrysler, while at the same time, the company was spending US$134 million on advertising, saying that it needs to keep its image alive. I endorse advertising, but I fear that they might have wasted a lot of money.

The first error is the use of jargon. In general terms, most people might understand inches and centimetres, or pounds and kilograms. So if we were to say that for $10 you can receive a bar of gold that is 2 cm (or inches) square, you would be able to comprehend this. One can visualise what is on offer. What if you were told that this bar were 100 kg in weight? If you have basic knowledge, you would be amazed, because something so small, to weigh so much, would be out of this world. However, is $10 a fair price for a small lump of gold? At this point, given that you know a bit about gold, you would ask if it is plated, or how many carats it is. If you knew a great deal about gold, you would be either suspicious or amazed at this price. The offer would trigger many thoughts. However, for the average person who is not a professional jeweller, this offer would only be amazing if they were assisted to comprehend the $10 offer, by comparing it with the market value. So the ad would need to say, ‘A $500 bar of gold, for $10 if you purchase today’. Now we have a clue by comparison.

The first error is the use of jargon. In general terms, most people might understand inches and centimetres, or pounds and kilograms. So if we were to say that for $10 you can receive a bar of gold that is 2 cm (or inches) square, you would be able to comprehend this. One can visualise what is on offer. What if you were told that this bar were 100 kg in weight? If you have basic knowledge, you would be amazed, because something so small, to weigh so much, would be out of this world. However, is $10 a fair price for a small lump of gold? At this point, given that you know a bit about gold, you would ask if it is plated, or how many carats it is. If you knew a great deal about gold, you would be either suspicious or amazed at this price. The offer would trigger many thoughts. However, for the average person who is not a professional jeweller, this offer would only be amazing if they were assisted to comprehend the $10 offer, by comparing it with the market value. So the ad would need to say, ‘A $500 bar of gold, for $10 if you purchase today’. Now we have a clue by comparison.

The Chrysler ads often mention the 317 kilowatts. Most people know what a kilo is. And they have heard the term ‘Watt’ used in relation to light-bulbs. Yet, when the phrase/measure is combined, it does not form a picture in one’s head. Of course, a real automotive pro would understand. But this ad is not directed at the pro. It is mass-marketed. The car is being sold to the average family driver or executive. The average person would not be able to imagine what this really means. This is failing in terms of communication. The best form of communication takes a message from one person, and implants it in the head of another (while evoking emotion at the same time).

So here we do not know what 317 kw really means. The second aspect where this ad fails is in what I call the ‘comparison’. The consumer would only say ‘wow’ if they knew what their current vehicle was rated at. For example, if the average Holden Commodore is only 17 kw, and this Chrysler is 317 kw, we know from general maths that this has 300 more. So first, tell the consumers what they are driving, so that they have a comparison. But this is useless unless you give consumers a reason to care. The ‘so what’ test comes next. So what that my car is 17 and this one is 317? Unless we can convert that into something we can visualise, then there is no connection in the communication. Of course, if it transpired that the Holden is 316.5 kw, and this one is 317 kw, that would spark a whole new set of questions.

The advertiser might do well to put that in terms of, ‘If your Holden and this Chrysler raced from Sydney to Perth or from New York to LA (the geography has to make sense to the reader), then by the time you leave your front door, the Chrysler would already have reached Alice Springs (Texas). And now this has an ‘amazing’ factor about it. Yet, the consumer will have to wonder ‘so what?’ Sounds fast and powerful, but my local speeding laws prohibit me from travelling any faster than the local speed limits, which are so low anyway.

And those who know a bit about cars will start to wonder what kind of fuel this car would consume if it is this amazing. There are dozens of other factors that would come into play. All the while, a billboard ad must contain no more than a few words, so it’s a tough assignment.

The internet version of the ad, as shown below, also mentions torque. The average driver whom they are trying to attract will not be able to really comprehend this. Sure, if asked casually at a party, they would pretend to know about it, because they do not want to appear ignorant, but place people in a room and ask them to explain what all these technicalities really mean, and they will fail. Which means that the advertiser has failed. Sure, we can boast in advertising, and we could hope that it would rub-off on the consumer, but in the end, people will feel lost.

The second-last strip worries me. It says that the Chrysler can go from zero to 100 kilometres per hour ‘in low 5 seconds’. This is either sloppy writing or slimy writing. The uninitiated is being conned. The average reader might assume that it is 5 seconds. Much like the silly ads that say, ‘in five short weeks, you can lose weight’. Five weeks are five weeks. There are no such things as five short weeks. And banks say ‘In five low repayments of $10’. Ten dollars are ten dollars. There can be no such things as low ten dollars. Hence, most people will presume that the Chrysler can reach 100 km/h in 5 seconds. Yet I suspect that they mean in the ‘low fives’ like people say, ‘I am in my low thirties’, which is like 35 years old. And so now the company commits yet another sin by misleading.

I trust that this article has given you a brief introduction to the complexity of advertising.

Jonar Nader is a management consultant who areas of expertise include adverting, marketing, and branding. His observations about customer service and consumer behaviour can be found in his book, ‘How to Lose Friends and Infuriate People’.

Jonar Nader is a management consultant who areas of expertise include adverting, marketing, and branding. His observations about customer service and consumer behaviour can be found in his book, ‘How to Lose Friends and Infuriate People’.

Comments are closed.