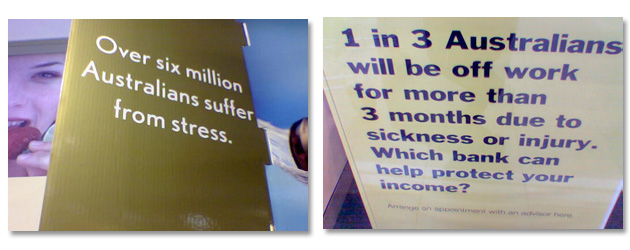

I happened to see this large poster at a pharmacy, promoting vitamin tablets. Could it be true that over six million Australians suffer from stress? That’s almost half the workforce. It means that one in two people is suffering from this ailment. One of us is not well. I feel fine. It must be you.

I happened to see this large poster at a pharmacy, promoting vitamin tablets. Could it be true that over six million Australians suffer from stress? That’s almost half the workforce. It means that one in two people is suffering from this ailment. One of us is not well. I feel fine. It must be you.

The Commonwealth Bank a few doors down said, ‘One in three Australians will be off work for more than three months due to sickness or injury.’ That’s a huge statistic. Considering the types of work that Australians mostly perform, I’m surprised it’s that high. What must the figure be in places like China where the workload is heavier and more dangerous? Maybe it’s no so bad over there because people don’t have compo and insurance and sick days and compassionate leave and stress leave.

The Commonwealth Bank a few doors down said, ‘One in three Australians will be off work for more than three months due to sickness or injury.’ That’s a huge statistic. Considering the types of work that Australians mostly perform, I’m surprised it’s that high. What must the figure be in places like China where the workload is heavier and more dangerous? Maybe it’s no so bad over there because people don’t have compo and insurance and sick days and compassionate leave and stress leave.

If 50% of the workforce is stressed out, it would not be an unfair question to ask each person what they mean by stress. It’s one of those words like ‘depression’ or ‘boredom’. People use it to mean different things.

In ‘How to Lose Friends and Infuriate Your Boss’, the first chapter touches on the topic of stress, wherein I say:

KILLER DISEASES

Collectively, we entered the twenty-first century carrying a doctor’s certificate. It said, ‘Suffering from stress. Light duties prescribed.’ What does it mean to be ‘stressed out’? What causes us to feel pressured, overworked, and underpaid? Every ten years or so, we learn about a new wave of occupational hazards. Most recently, public liability has become so expensive that community events have had to be cancelled and small businesses have had to be closed. Exorbitant insurance premiums have been fuelled by our litigious society, whose members no longer take responsibility for their own actions — even when walking across a field. Back in the 1990s, employers discovered how costly it could be to handle grievances and ‘emotional damage’ in relation to sexual harassment and unfair dismissal. In the 1980s, employers refused to believe that ‘repetitive strain injury’ was a serious ailment; not until the courts awarded astronomical payouts to victims of soft-tissue injury. All of a sudden, ‘ergonomics’ entered the vernacular. In the 1970s, employers and insurers were learning about back-pain and whiplash. For private investigators, business boomed as they spied on unethical workers for whom ‘compensation’ was another word for ‘get-rich-quick’. Lawyers convinced victims to try their luck, promising ‘no win, no fees’. Despite employers’ best efforts to appease unions, to placate environmentalists, and to satisfy insurance companies, it seems that our places of work are more dangerous than ever. Stress is the new killer that affects workers’ mental and physical health. It destroys both productivity and profitability.

Is it conceivable that, despite earnest attempts to improve occupational health and safety, we have entered an era in which the greatest threat to our workforce is an ill-defined intangible disease that emanates from work itself? Could it be that workers are more inclined to suffer from stress because they are uncertain about their future and because they are not passionate about their work?

Although we can point to many factors that fuel stress, we must find out what triggers it. In my search to understand the essence of stress, I have come to disagree with popular medical definitions. I define occupational stress as a condition resulting from our inability to reconcile our capability with our authority. This means that stress is ignited when we can see a solution to a major problem, and we know that we are capable of fixing that problem, but we have no authority to do so. We are shackled by bureaucracy.

Stress leads to frustration, which in turn leads to a debilitating disease called ‘depression’. I define depression as a condition resulting from our inability to reconcile our inadequacy with our responsibility. This means that depression consumes us when we realise that we are unable to do anything about our own problems. As a result, we believe that our problems will never go away.

STRESS TEST

I have devised a stress test called the ‘elasticity of command’. It enables me to determine an individual’s propensity to suffer from occupational stress. I draw on the analogy of giving employees a piece of elastic to measure the distance between them and the nearest colleague who can obstruct a project unnecessarily. Employees are then asked to compare that by measuring the distance between them and their commander (the boss) — whose responsibility it would be to facilitate a smooth transition for the project.

If the boss is reachable and responsive, the stress level is said to be minimal. If the boss is unreachable and unresponsive, the stress level is said to be extreme. Stress becomes ‘frustration’ when those who can obstruct us are more powerful than our boss. In industries where everything is processed in real-time, we must be given the tools to make decisions in real-time. Using ‘elasticity of command’, we can see that the person who is ultimately responsible for work-related stress is none other than the boss (whether it be our own boss, or someone further up the ladder). Bosses, too, can suffer from stress if their superiors are unreachable and unresponsive.

It would be convenient to blame ‘globalisation’ or ‘politics’ or a myriad of external factors for today’s stressful work environments. Ultimately, it all boils down to the boss. If you are the boss, or aspire to become the boss, it is important to equip yourself with the skills that will be demanded of you in the future. Otherwise, you could perpetuate this problem into the next decade.

Comments are closed.