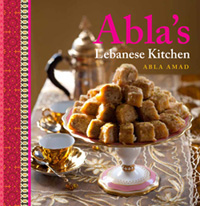

Naturally, any well-written book about high technology and mathematics is of interest. Cookbooks are delightful too, especially if they have excellent photographs of delicious creations. In the absence of tantalising photographs, a cookbook must be accurate and simple to follow. My latest favourite is ‘The Lebanese Kitchen’ by Abla Amad. This book wins hands down for its simplicity and accuracy. Perhaps my well-developed palate (thanks to my mother) for Lebanese food has made me overly critical of all Lebanese restaurants and cookbooks. However, Amad’s masterpiece is deserving of praise.

I also enjoy books like Lewis Carroll’s ‘Alice in Wonderland’ (which was first called ‘Alice’s Adventure Under Ground’ when it was written in 1865). I enjoy this book because it has many hidden messages. I was fascinated about how it came to be written, including how it was illustrated and published, and how Carroll negotiated with his publishers. By the way, many people do not know that Carroll’s real name was Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (born 1832). He was a mathematician who enjoyed the processes of logic, and engaged in photography, art, theatre, religion, medicine, and science. Hollywood still makes movies about Alice.

With my love for comedy, I particularly delve into books about the subject, including ‘Bring me Laughter’ by Bruce Crowther and Mike Pinfold. I read manuscripts from stage and screen — mostly from the BBC.

Autobiographies are interesting, except that I rarely have the time to read huge tomes as they often are. If the books are short, I am more likely to pick them up. For example, I liked learning about John Cleese from a book by Jonathan Margolis called ‘Cleese Encounters’.

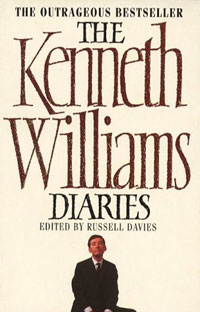

Published diaries are far more interesting. ‘The Kenneth Williams Diaries’, edited by Russell Davies, give an insight into Williams’ life. (Both Cleese and Williams are mentioned in my Favourite Comedy page at my website). Williams kept a diary since he was fifteen years old, leaving behind 43 years’ worth of diaries. He said that, ‘Diaries are written so that one has a record of events, and because there are certain events one wants to remember. There is perhaps also the element of the confessional in them, and that isn’t a bad thing in my eyes. It has certainly eased my loneliness.’ His last diary entry in April 1988 had many people speculate about his death. His entry ends with an explanation of his back pain and stomach trouble, wherein he describes it as ‘torture’. The last line from his diary that contained four million words read, ‘…what’s the bloody point?’ His close friends could not accept that he might have committed suicide.

Published diaries are far more interesting. ‘The Kenneth Williams Diaries’, edited by Russell Davies, give an insight into Williams’ life. (Both Cleese and Williams are mentioned in my Favourite Comedy page at my website). Williams kept a diary since he was fifteen years old, leaving behind 43 years’ worth of diaries. He said that, ‘Diaries are written so that one has a record of events, and because there are certain events one wants to remember. There is perhaps also the element of the confessional in them, and that isn’t a bad thing in my eyes. It has certainly eased my loneliness.’ His last diary entry in April 1988 had many people speculate about his death. His entry ends with an explanation of his back pain and stomach trouble, wherein he describes it as ‘torture’. The last line from his diary that contained four million words read, ‘…what’s the bloody point?’ His close friends could not accept that he might have committed suicide.

![]()

‘The Letters of Vincent van Gogh’, edited by Mark Roskill, help to explain how some people cope with passionate pursuits. Vincent’s paintings are attractive. However, I cannot agree with their current exorbitant value. I cannot see that his paintings are worth millions of dollars, except for the fact that one would be buying a piece of passion. Vincent reveals madness in his life. His letters to his brother, Theo, gave us clues about his poverty and his fixation with art. I enjoyed this book not so much from an artistic angle, but for what it has taught me about the meaning of passion for one’s work. As sad as his life was, Vincent was a model for anyone who decides to dedicate every fibre to a project. If Vincent had ten cents to his name, he would not hesitate to buy a paintbrush, knowing full well that he would go without dinner for a week. An example of this is given in a letter to his brother in October 1888 wherein he writes, ‘Thank you for your letter, but I’ve had a poor time of it these last days; my money ran out on Thursday, and so it proved a hellishly long time between then and Monday noon. During these four days I have lived mainly off coffee, 23 cups of it, with bread…’ No sooner his brother sent him money, than he spent it all that afternoon on frames, canvas, and brushes.

‘The Letters of Vincent van Gogh’, edited by Mark Roskill, help to explain how some people cope with passionate pursuits. Vincent’s paintings are attractive. However, I cannot agree with their current exorbitant value. I cannot see that his paintings are worth millions of dollars, except for the fact that one would be buying a piece of passion. Vincent reveals madness in his life. His letters to his brother, Theo, gave us clues about his poverty and his fixation with art. I enjoyed this book not so much from an artistic angle, but for what it has taught me about the meaning of passion for one’s work. As sad as his life was, Vincent was a model for anyone who decides to dedicate every fibre to a project. If Vincent had ten cents to his name, he would not hesitate to buy a paintbrush, knowing full well that he would go without dinner for a week. An example of this is given in a letter to his brother in October 1888 wherein he writes, ‘Thank you for your letter, but I’ve had a poor time of it these last days; my money ran out on Thursday, and so it proved a hellishly long time between then and Monday noon. During these four days I have lived mainly off coffee, 23 cups of it, with bread…’ No sooner his brother sent him money, than he spent it all that afternoon on frames, canvas, and brushes.

Comments are closed.