Half way through Year-Nine at high school, the first Asian student joined our class. What a shock. What a novelty. He was fifteen, with the soulful glance of a wise man. The frightened boy did not say much. Actually, he hardly said anything at all… notwithstanding he could not speak English barring a few words including Hello, Yes, No, My name is Jim.

Half the boys teased him — he was their source of amusement because everything about Jim seemed different. Those who were not poking fun at him, were not being kind; merely too self-absorbed to pay attention to a kid scared out of his wits. To my eyes, as a Lebanese boy who had experienced war and all its horrors in Beirut, I understood his silence. Jim was not quiet; he was confused. He was not gentle; he was exhausted. He was not polite; he feared an unprovoked attack. Those who thought he was always smiling, did not perceive that he was masking his shame. He was not squinting from the glare. Rather, he was holding back the emotions lest the sun’s rays shimmer off the tears welling in his eyes.

I befriended Jim, even though we never hung out after school. We never played together. We never bantered. Jim had no time for such things. Partly because he did not trust anyone, and partly because he was a boy on a mission. He had to find a way to survive the war… Jim was at war with his past, with his father, and with himself. He was not sure if life was worth living amidst daily humiliation and incessant burdens. Jim confided in me that I was his best friend. Really? How could I be the best friend, when we hardly spoke? As it turned out, that’s precisely what he appreciated most. I was the one person next to whom he could ‘be’ without having to justify his grief. He could sit next to me, devoid of jibes of curiosity. With me, there was no cross-examination. Jim valued the luxury of a few minutes of freedom. He needed to be devoid of thinking. He wanted to be free from feeling. He was a tortured soul whose heart and mind were gasping for air. He needed to breathe, because his past life was unfolding so thick and fast, and his future prospects were so grim, that he had no time for the present.

Fast-forward 33 years, and an Asian woman casually enters my life at a corporate Christmas function. Her name is Pauline Nguyen. Everything about Pauline was refined — not in terms of airs and graces, but in how she engaged, how she spoke, how she communicated, how she listened. Pauline was refined as one would expect a Rolex to be refined. Fine tuned. Well tuned. In tune. How could this young Vietnamese woman be so all-together? Sharp. Present. Observant. Kind-hearted. Talented. Fit and healthy. I figured that Pauline was a product of hard work. People are not made like this. It takes energy and effort to grow one’s spirit of gratitude. Pauline was like a well-oiled intricate timepiece.

Fast-forward 33 years, and an Asian woman casually enters my life at a corporate Christmas function. Her name is Pauline Nguyen. Everything about Pauline was refined — not in terms of airs and graces, but in how she engaged, how she spoke, how she communicated, how she listened. Pauline was refined as one would expect a Rolex to be refined. Fine tuned. Well tuned. In tune. How could this young Vietnamese woman be so all-together? Sharp. Present. Observant. Kind-hearted. Talented. Fit and healthy. I figured that Pauline was a product of hard work. People are not made like this. It takes energy and effort to grow one’s spirit of gratitude. Pauline was like a well-oiled intricate timepiece.

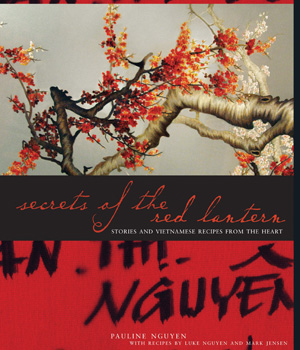

A short while later, I saw a new dimension to Pauline Nguyen — the creative performer, the successful business woman, the doting mother, the supportive wife, the dreamer, the friend. From where does such a lotus flower spring? I think I know the answer to this question. Her father speaks of it when he describes the role he played in raising his children. I read what he said in Pauline’s book called, ‘Secrets of the Red Lantern’. It is a book in which Pauline, eager to scribe her story for her daughter, outlines the agony and tribulation of the Nguyen family’s escape from Vietnam on a small boat. Pauline and her clan are ‘boat people’. She and her family had endured the terror of escaping a bloody war. Unfortunately, the past chased them across the waters to the refugee camp, and later into their home in Cabramatta. The past had turned her father into a train-wreck. He became bitter, angry, and violent — not just part of the time, but every minute of every day. Pauline had to struggle with her family’s nemesis: fear! The terror was not a cloak. Rather, it was an indelible ink-stain, as permanent as the colour of one’s skin.

In her book, ‘Secrets of the Red Lantern’, Pauline wrote, ‘I cannot remember any time when fear did not lurk over my shoulder. Fear seeped through every window, rose up from each shiny floorboard and spilled through the dead cracks in our walls. It hovered over our beds while we were sleeping.’

In her book, ‘Secrets of the Red Lantern’, Pauline wrote, ‘I cannot remember any time when fear did not lurk over my shoulder. Fear seeped through every window, rose up from each shiny floorboard and spilled through the dead cracks in our walls. It hovered over our beds while we were sleeping.’

To admire Pauline Nguyen, we must learn about the furnace whence she was fired. Her father was struggling to survive. His war was always raging, and his collateral damage was inflicted upon, and absorbed by, those whom he loved most. Pauline and her mother and brothers did not grow up with peace in their heart. They hankered for respite and prayed for freedom. Neither was within reach, because hell is a furious chamber wherein glimmers of hope are snuffed out.

Pauline explains the sacrifices. ‘We worked at the restaurant seven days a week before and after school, stopping only to finish our homework and complete household chores. Outside activities included maths school, Vietnamese school, cooking school, debating, and martial arts. We did all this and had to get top grades as well.’ In this regard, Pauline reminds me of Jim — the Asian boy who stood out in our class as the solitary Asian who copped harassment all day long for what he looked like, what he ate, what he had, and what he could not afford. The boy who could not speak English when he entered our class mid-way through Year-Nine, was acing his subjects within a matter of months. That did turn some heads. All of a sudden, the students realised that the slanty-eyed foreigner had a brain far superior than theirs. Thereafter, a modicum of reverence had surfaced for Jim, the quiet achiever. As his friend, I understood why he did so well at school. Jim had no life. He neither knew the meaning of ‘social calendar’ nor how to kick a ball, let alone catch one. His father demanded superior grades. Anything less than an ‘A’ resulted in severe punishment. In ‘Secrets of the Red Lantern’ Pauline describes her own angst in relation to her father’s demand for academic excellence.

‘My father placed tremendous pressure upon us from an early age — any average result was a failure in his eyes. The knowledge of this lingered over our heads like a cheerless cloud that never lifted. He sent us to strict same-sex private Catholic schools, which was a challenge in itself. But report time was the worst. Twice a year from the age of seven until thirteen, we would bring home our school reports with total fear and loathing. Assisted by his favourite billiard stick, the stiffest, shiniest one, my father would cane us once for every “B” grade that we held. For every “C”, he caned us twice… To shed a tear or release a whimper at anytime throughout this ritual meant a further beating to nullify our weakness. I cried only in private, knowing that the pain and bruising usually got worse before it got any better.’

Pauline then explains, ‘By the time we reached high school, the private canings stopped and a new punishment was introduced — public humiliation. While our friends lived their teenage years going out, discovering life and having fun, my father forbade us to go anywhere. He installed deadlocks on every major door of our house — front door, back door, living room door, dining room door and bedroom doors. It would have been impossible for a thief to penetrate — let alone for any child to escape. Our lives consisted of school, restaurant, sanctioned activities and home. He tolerated nothing else. My father controlled every hour of our day, and when any situation fell out of his control, we suffered the full force of his anger.’

Eventually Pauline ran away. She lived the life reserved for intelligence agents or gangsters who were ensconced in a witness-protection program. Pauline lived in fear of being found and dragged back home. She had escaped, but from what was she running? It took her a long time to understand that she could not run from herself.

In ‘Secrets of the Red Lantern’ Pauline wrote about the time her mother had pleaded with her to reunite with her father. ‘I wanted my fears forgotten, not faced up to. I resented my mother for asking me to do this. No way was I ready to see my father again. Anxiety overwhelmed me as it always did. It came in waves, at times more bearable than others — paranoia, irritability, insomnia, nausea, apprehension. The years of living with fear and oppression had programmed me to internalise all my problems, keeping my pain and frustrations in the pit of my gut. I misled everyone, including myself, by projecting an exterior of strength, confidence and determination. But anger was the real culprit that fuelled me. Anger fooled me into thinking that I could cope, that I was a tough nut — nothing could break me. On the outside was all hardness. On the inside was red raw vulnerability rubbing away at nerves damaged long ago. The emotional ulcer that grew within, began to fester. The persistent fumes of bitterness suffocated me. What a mess I had grown up to be. Parents do not realise that the unhealed injuries they carry themselves, inevitably pass down to their children. Unresolved trauma has a way of transmitting across many generations.’

In ‘Secrets of the Red Lantern’ Pauline wrote about the time her mother had pleaded with her to reunite with her father. ‘I wanted my fears forgotten, not faced up to. I resented my mother for asking me to do this. No way was I ready to see my father again. Anxiety overwhelmed me as it always did. It came in waves, at times more bearable than others — paranoia, irritability, insomnia, nausea, apprehension. The years of living with fear and oppression had programmed me to internalise all my problems, keeping my pain and frustrations in the pit of my gut. I misled everyone, including myself, by projecting an exterior of strength, confidence and determination. But anger was the real culprit that fuelled me. Anger fooled me into thinking that I could cope, that I was a tough nut — nothing could break me. On the outside was all hardness. On the inside was red raw vulnerability rubbing away at nerves damaged long ago. The emotional ulcer that grew within, began to fester. The persistent fumes of bitterness suffocated me. What a mess I had grown up to be. Parents do not realise that the unhealed injuries they carry themselves, inevitably pass down to their children. Unresolved trauma has a way of transmitting across many generations.’

Eventually, Pauline travelled to Europe. ‘Paris had opened my eyes to the abundant possibilities that my life could hold. I blew [Paris] a kiss, bid her farewell and thanked her for everything. Paris had allowed me, for the first time in my life, to have fun…’

From her gloomy past, Pauline Nguyen had blossomed. How was this possible? Other people in her predicament might have broken down and bowed out from life. Pauline Nguyen is all the better for her struggles. Her father describes it thus: ‘Do you know why Buddha sits on a lotus flower? Nothing is as beautiful as a lotus flower. Out of watery chaos it grows, emerging from the depths of a muddy swamp and yet remains pure and unpolluted. So pure you can eat it — all of it, the flowers, the seeds, the leaves, the roots. But the lotus has another characteristic. Its stalk you can bend in two, but it cannot easily break. It has strong, tenacious fibres that hold the plant together…’

From her gloomy past, Pauline Nguyen had blossomed. How was this possible? Other people in her predicament might have broken down and bowed out from life. Pauline Nguyen is all the better for her struggles. Her father describes it thus: ‘Do you know why Buddha sits on a lotus flower? Nothing is as beautiful as a lotus flower. Out of watery chaos it grows, emerging from the depths of a muddy swamp and yet remains pure and unpolluted. So pure you can eat it — all of it, the flowers, the seeds, the leaves, the roots. But the lotus has another characteristic. Its stalk you can bend in two, but it cannot easily break. It has strong, tenacious fibres that hold the plant together…’

Pauline’s father then explains, ‘My children are lotus flowers… Like the lotus flower, all of you have grown out of the mud of your origins. You grew out of the aftermath of war, you grew out of Cabramatta during its murkiest time — and you grew out of me. I was mud. Our family was mud. I was shit. I am very lucky to have you all.’

Pauline’s father then explains, ‘My children are lotus flowers… Like the lotus flower, all of you have grown out of the mud of your origins. You grew out of the aftermath of war, you grew out of Cabramatta during its murkiest time — and you grew out of me. I was mud. Our family was mud. I was shit. I am very lucky to have you all.’

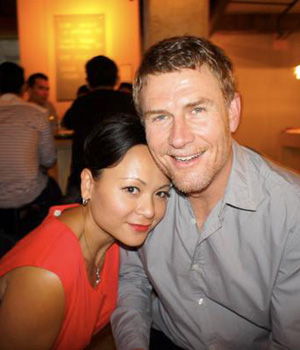

Within the 344 pages of ‘Secrets of The Red Lantern’ (published by Murdoch Books Australia) are Pauline’s precious memories, interspersed between hitherto secret family recipes, enriched with commentaries by Pauline’s husband (chef Mark Jensen) and Pauline’s brother (chef Luke Nguyen).

The book chronicles: the struggles of the past; the raging anger; and the family’s anguish. It describes the bond between Pauline and her husband Mark, and how he entered the family and was embraced as the fourth son. We learn about the formation of the world-famous and highly acclaimed Red Lantern restaurant that now enjoys a stellar trajectory of its own.

Squeeze the pages, and you will discover tears — yours as the reader, mixed with Pauline’s and those of her family — none of whom emerged unscathed. From the quagmire, Pauline and her brothers grew like lotus flowers — strong, full of beauty, and a sight to behold, giving us all hope in the human spirit. From adversity, Pauline was able to break the barriers and arise triumphant. Her journey is not over. She is still a young woman, a mother, a wife, a teacher, an inspiration to others, and a student with an insatiable appetite for all things delicious — art, travel, adventure, newness, family, and friendships.

Hats-off to boat people.

A salute to the Nguyen family.

A toast to Pauline.

An embrace to life’s bitter-sweet moments.

Without hardship, we might not forge the strength to overpower the demons. Sometimes, the tormenting ghosts are lurking in our past. We need to vanquish them, before they reach across the decades to strangle us. The lonely and arduous pilgrimage to our youth, often takes us through the hazardous and dark burrows of our mind, into the muddy waters (and through the ‘shit’ as Mr Nguyen describes it) to face our aggressors; perchance to return to the present, as heroes of our crusade.

The past is solid. It has no reason to budge. Alas, it needs to be defeated if we are to return with our head held high. Pauline Nguyen is a humble woman whose vibrancy is not born of ego. Rather, it seems to me, she radiates the after-effects of a radio-active past from which she has returned the victor.

Racists often instruct foreigners, ‘Go back to where you came from!’ That’s exactly what Pauline and her family did. They dared to embark upon an expedition of self-discovery, desperate to combat anger, sadness, death, war, struggle, sorrow, injustice, fear, poverty, and despair. They returned nursing a precious gift for themselves and for us all. That gift? Joy in abundance!

P.S. You can purchase copies of the book from Red Lantern restaurants (which incidentally serve amazing food) or order on-line from Red Lantern’s website. Chef Mark Jensen also has a stunning book called ‘The Urban Cook’. Luke Nguyen’s videos and books are also available from Red Lantern’s website. You can learn more about Luke at his YouTube Channel.

Comments are closed.